I explore the Fourth Song of the Suffering Servant. The goal is to unpack the themes that resonated with the original audience. From there, we can bridge our experience of the text as people become aware of the Christian story. It will be worthwhile to hear this passage as we explore it. After this hearing, I want to highlight the themes of appearance, reaction to suffering, and God’s initiative in suffering:

We are contemplating poetry, which “cannot be reduced to a rational formula” (Brueggemann 146). As we hear of how suffering and guilt can be deployed from one to another and how suffering makes healing possible for others

At the beginning of this passage, one can assume that this suffering resulted from punishment. The prophet hints at something new being presented, “From this time forth I make you hear new things, hidden things which you have not known” (48:6b). This new thing is now revealed at the opening of this pericope as it is poetically stated “for that which has not been told them they shall see, and that which they have not heard they shall understand” (52:15). These sentiments repeat at the opening of the next chapter, “Who has believed what we have heard?” (53:1) Yahweh is presenting something new in the suffering servant. The question witnesses “the power of Yahweh, the destiny of the servant, and the faith of the witnessing community” (Brueggemann 146).

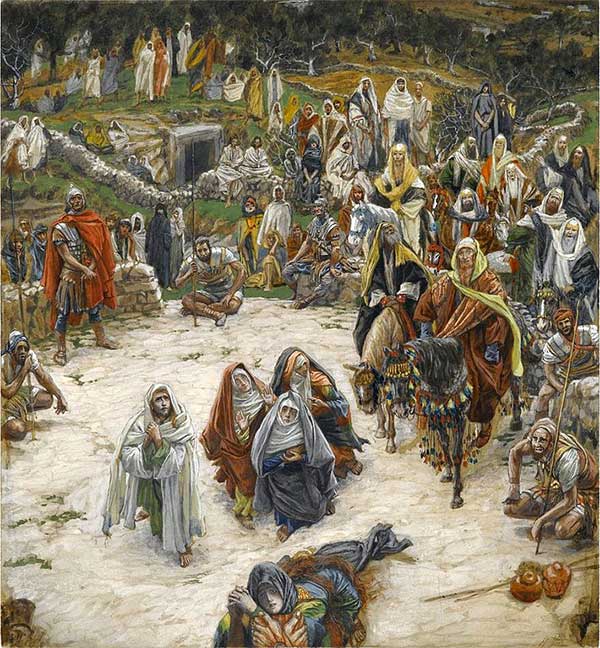

The servant is described as unrecognizable and had “no form or comeliness that we should look at him” (53:2). In the Old Testament world, a man’s integration to society was crucial. To be estranged was to be “an idiot in the Greek sense of the world” for people “regarded him as an isolated fanatic” (Knight 170). There was a theory that the servant suffered from leprosy as “leprosy can eat away people’s limbs and features, and one reason why the human instinct is to shut lepers away is that the sight is too much for people to cope with” (Goldingay God’s Prophet 142). This may not necessarily be factual. At the same time, the imagery carries the sentiments of being estranged due to disfigurement of physical appearance.

The crowd’s tone suddenly changes when they recognize their suffering in the servant’s suffering. The crowd speaks of how the suffering of this servant bore their griefs (53:4). He was wounded for their transgressions, bruised for iniquities, and that his suffering was the chastisement that made them whole (53:5). The crowd is bewildered and grateful in their account of the servant as the servant’s actions directly impact them as “one life can be vulnerable enough to permit restoration of another (Brueggemann 146).

The crowd also recognizes the servant’s innocence. The imagery of the crowd as sheep who “have gone astray” (Isaiah 53:6) is a stark contrast to the servant who knew the course he must take as he was a “lamb led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent so he opened not his mouth” (Isaiah 53:7) and highlights the innocence of the servant.

The focus then elevates suffering to something greater. Through this obedient suffering, an offering was made (53:10). Through suffering, new life sprouts. This is in contrast to when the prophet was a young plant who had roots in the dry ground (53:2). The obedient suffering rendered many blessings. The servant bore the sins of many and continued to offer prayers for them (53:12). Yahweh was pleased. In the servant he found an “effective sufferer” (Brueggemann 144, 148). His humiliation moved to exaltation and invited the hearers to the deep abiding trust of Yahweh.

There is a cadence at the end of this pericope as the servant is exalted (Isaiah 53:12). The servant will be given his portion among the great. He will be worthy of making intercession because of his obedience in suffering. To a Jewish audience, exaltation is “in whatever form it arrives.” For the Christian, this exaltation resonates with the Resurrection of Christ.

This pericope is a mystery where one stands in awe, and “neither Christian nor Jew knows how to decode this poetry” (Brueggemann 149). What is certain is that this poem demonstrates God’s movement from guilt to healing through the obedient act of a servant. Jews and Christians share this certainty, though they see it from different angles. The poetry offers “a confession, an admission, a dazzlement, and an acknowledgment” that resonates with Jews and Christians (Brueggemann 146).

In the next post, I will explore how we understand the Suffering Servant in the liturgy.

You are welcome to leave a reply.