I first saw the city of Jerusalem in October 2019. I stood at the Garden of Gethsemane. It was magnificent to behold! I saw the gate where Jesus entered the holy city. Jewish tradition says that Jesus entered the Holy City from the Golden Gate. It is also known as the East Gate or Mercy Gate.

Many believe that when Christ returns in glory he will enter through this gate. It has remained closed for over four centuries.

Jesus had his eyes set on Jerusalem. After the confession of Peter, Jesus traveled from Caesarea Philippi, in the northernmost part of the Holy Land toward Jerusalem. He traveled to the place where the common Passover was celebrated to be the true Lamb to offer his life as the perfect sacrifice. The goal of Jesus was utter fidelity to the Father’s will.

All of us are on a similar journey with the Lord. That journey is marked with intensity at the start of Holy Week. This is a difficult journey because it is a journey within. We travel with the Lord to the center of our hearts, where he must reign and where we all cry Hosanna.

Hosanna is a plea with one’s whole being to the divine. It is a plea to be saved. The king has entered his city and all cry: save us!

Pope Benedict XVI comments on the word Hosanna:

This festive acclamation, reported by all four evangelists, is a cry of blessing, a hymn of exultation: it expresses the unanimous conviction that, in Jesus, God has visited his people and the longed-for Messiah has finally come. And everyone is there, growing in expectation of the work that Christ will accomplish once he has entered the city.

This day marks the beginning of Holy Week where we will watch Christ in his unshakeable obedience to the Father. Jesus enters riding on a donkey. This scene fulfills Zechariah’s prophecy:

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter of Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on an ass, on a colt the foal of an ass. He shall banish the chariot from Ephraim, and the horse from Jerusalem; the warrior’s bow shall be banished, and he shall proclaim peace to the nations. His dominion will be from sea to sea, and from the river to the ends of the earth (9:9-10).

As he rides on the donkey into the holy city, the prophet declares that Jesus will be the image of his first beatitude. He is poor in spirit. He will be the one who is king of the poor. He is the poor one in the midst of the poor.

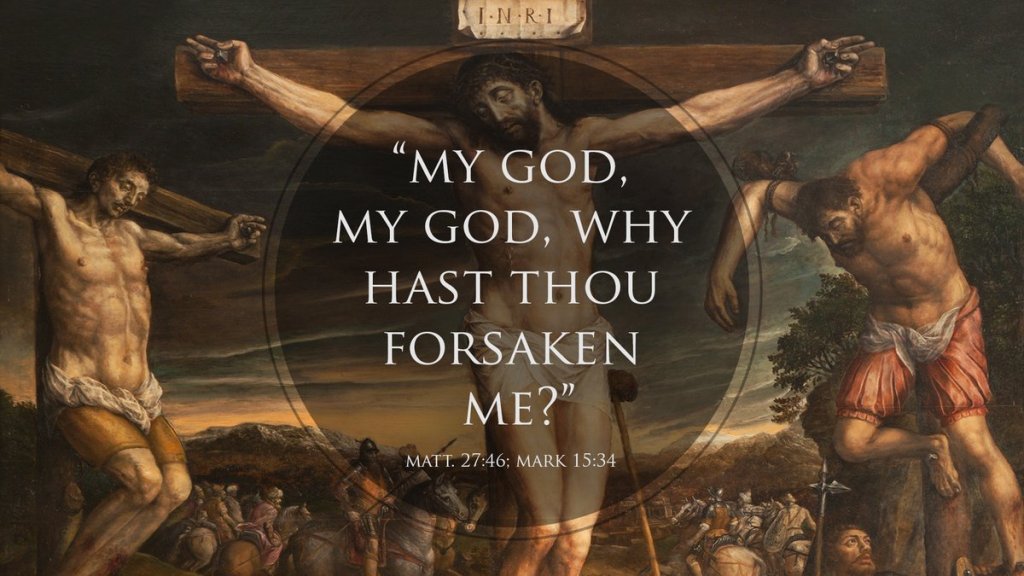

Yet, while king of the poor, he is exalted on high. On his cross, he will say something that deserves our uninterrupted attention. He will cry out to his Father. We give voice to this in the liturgy. In all liturgical cycles, we sing Psalm 22.

When Jesus prayed the opening of the twenty-second psalm, he is recorded as crying, “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?” The first half of this sentence is in Hebrew, “Eli, Eli…” while the second half is in Aramaic. Yet, the bystanders at Jesus’ cross thought he was calling the prophet Elijah. They misheard him as they all had during his public ministry. The atmosphere in Jesus’ time was saturated with many eschatological ideas. It was popular among Jewish thinking that Elijah was supposed to return and introduce the Messiah.

Elijah is mentioned twenty-seven times in the Gospels. He was like a patron saint to the Jews, an eschatological figure expected to mark the coming of a Savior for God’s people. When Elijah did not appear, the bystanders had more reason to believe that Jesus was the false Messiah, a fault that belonged to their mishearing.

When we hear Psalm 22 with Christian ears, our understanding is modulated to a new key. When we hear this cry from Jesus’ lips we hear an intimate dialogue between Jesus and the one he called Father. We hear Christ as the one who is laughed at by his enemies, whose garments are divided, whose bones are licked by the dogs. This cry from the cross is not so much a cry from an individual as much as it is Christ who cries for all of suffering Israel.

As Jesus cries from the cross “he is taking upon himself all the tribulation, not just of Israel, but of all those in this world who suffer from God’s concealment” (Ratzinger, Jesus of Nazareth, vol. 2, 214).

In one sense, this lament is particular to Israel’s lament in which God’s capacity to govern creation is close to full shut-down as the “Fatherlessness of the Son is matched on that Friday by the Sonlessness of the Father” (Bruggemann. From Whom No Secrets Are Hid, 102-103). God allows himself to feel utter separation from his creation.

In another sense, this cry is the manner in which Jesus plunges into the depth of human suffering and makes himself present to all those who are in a state of God-forsakenness. As he enters into solidarity with all who suffer, for all time and history, “he takes their cry, their anguish, all their helplessness upon himself – and in so doing he transforms it” (Ratzinger, Jesus of Nazareth, vol. 2, 214).

The sudden and deliberate praise which we find at the end of Psalm 22 is the glorification of Christ at his resurrection. The Lord Jesus rises from the tomb and praises his Father with all the nations that will surround him.

As we sing this psalm on Palm Sunday, the people of the assembly become the ‘I’ and ‘we’ of the psalmist. The assembly is caught up, united, and grafted into the voice of Christ, as the Body of Christ, addressing the Father in one unison voice.

When we cry out “My God, my God …” we cry out as the Body of Christ, not only being united to the Messiah in his single sacrifice on Calvary, but we are also intimately bound to our brothers and sisters who cry out in our modern day injustice.

We cry out on behalf of a humanity that feels isolated and desires intimate communion with God. We cry out like the psalmist’s ancestors, like the Lord, and as a chosen people. This cry comes from the depths of our human experience so that in our deliverance God can gather all nations with the past, present, and future, to praise him in his holy temple.

The words that Jesus prayed in the psalms “are now found on our lips, and so they must also be interpreted in the context of the unfolding pattern of our own lives, which will always be some version of the one and only story to which every Christian life is conformed: cross and resurrection” (Reid’s Psalms and Practice, 202-219).

When we pray this psalm on Palm Sunday, we are united with the words of Christ, his suffering, his resurrection, and ultimately his mission. Christ has transposed this psalm into a new understanding of his reckless love that is bound not only to suffering Israel, but to all humanity and to those who experience God-forsakenness. He will be peace. He will be King, not only of the Jews but from sea to sea, and from the river to the ends of the earth. A universal king for all.

Yes! Reckless love. Here’s a song to help us in this meditation of the love of God:

Hosanna to the Son of David!

You are welcome to leave a reply.